Historical Evidence

We have shipping and inventory lists for the New Hampshire settlements in the early 1630’s. The lists are printed on this website, but the 1635 inventory is very illustrative of personal weapons available from the company stores. I’ll present the list and then a brief discussion after.

Portsmouth List

- 14 small cannon

- 22 harquebuses

- 4 muskets

- 46 fowling pieces

- 67 carbines

- 6 pair of pistols

- 61 swords and belts

- 15 halberds

- 32 beaver spears

- 31 headpieces

- 50 flasks and bandoliers

- 2 firkins of lead bullets

- 2 hogshead of match

- 955 lbs of small shot

- 2 drums

- 15 recorders and hautboys

Berwick List

- 4 small cannon

- 9 harquebuses

- 47 muskets and bandoliers

- 28 fowling pieces

- 33 carbines

- 4 case pistols

- 36 swords and belts

- 6 barrels of shot

- 57 bullets

- 1 firkin lead bullets

- Barrel of match

- 1 drum

- 504 small shot

So, what can we conclude from this list (and generally the other lists include the same, nothing else added to what is here)?

- 18 small cannons between the two sites

- 256 handheld weapons (31 harquebuses, 51 muskets, 74 muskets, 100 carbines)

- Pistols were counted in pairs as cavalrymen generally carried two.

- Swords always came with belts. Not sure if the term “belt” is significant in referring to a waistbelt, or the term lumped together waist and shoulder carriages (baldric)

- “Headpieces” being included in military stores undoubtedly refers to helmets.

- No armor, breastplates, for example, are listed. No buff coats. However, the clothing lists have “moose coats” … a heavy leather coat? But if intended for military wouldn’t they be listed with military supplies? Hard to know.

- At this point we are not entirely sure what a “beaver spear” was, but it should be noted that no pikes are listed. Were these half pikes?

- Only match listed (and apparently quite a bit of it) and no flints, but carbines at the time were not matchlocks, being wheellocks or flint. In fact, according to Harold Peterson, match weapons were taking a serios decline in the 1630s. The fact that no flints are listed may only be a case that they were not as yet stored in bulk. All of this is speculation, of course, because the list does not indicate firing mechanisms.

- Music was considered important enough to have drums, recorders, and hautboys listed with weapons. They are included on the earlier lists as well

According to M. L. Brown in Firearms in Colonial America, by the 1630s firearms were defined by barrel length and caliber:

| Type | Barrel Length | Overall Length | Caliber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musket | 4’ | 5’2” | 12 bore (.75 cal.) |

| Caliver | 3’3” | 4’6” | 17 bore (.65 cal.) |

| Harquebus | 2’6” | 3’ | 17 bore (.65 cal.) |

| Carbine | 2’6” | 3’ | 24 bore (.58 cal.) |

From an article on archaeological evidence of firearms in Plymouth, the author says:

The musket is described as by the 1630 English Martial Arms list as a piece with a barrel four feet long, an overall length of five feet two inches and a bore of .74 caliber. A musket can be further described as a heavy military gun of the 16th to early 17th century with a matchlock. Muskets weighed approximately 16 pounds and required a forked rest to support it.

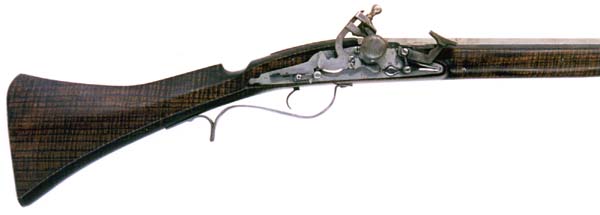

The arquebus or harquebus is a term that has been used in the past to describe a gun lighter than a musket and fired without a rest which by the middle of the 16th century became synonymous with the caliver. By the beginning of the 17th century, the term began to be used to designate a smaller wheellock weapon as opposed to a matchlock (Peterson 2000:13). Harquebus literally means hooked gun due to the hook like superset on the underside used to absorb recoil, by the early 17th century it referred to a long gun that was light enough to use without a forked support [my emphasis] and thereby favored by the cavalry (Kelso 1998: 14). The popularity of the arquebus appears to have waned in the first quarter of the seventeenth century as the carbine came into wider use.

The caliver is described as being a firearm that was lighter than a musket and was able to be fired without a rest, in some cases this was synonymous with the arquebus. The distinction between the two being that the caliver was more of a seventeenth century term while the arquebus is more common in the sixteenth to early seventeenth century. A piece of this type may have had a matchlock or flintlock firing mechanism. [my emphasis] Calivers were described as being three feet three inches long with a total length of four and one half feet with a bore of .654 caliber

In the seventeenth century, fowlers came in a long and short variety. Long fowlers were described as being five and one half to six feet long with a bore of approximately 65 caliber (Markham 85). Long fowlers, while very useful in hunting the abundant waterfowl in New England, are somewhat cumbersome to carry in militia. This did not stop them from being allowed, but at least in Plymouth, the barrel had to be less than four feet long.

Carbines were firearms with short, sixteen to 30 inch long barrels of full musket bore with either snaphaunce or wheelock locks. Carbines were usually carried by the cavalry with the ones from the early seventeenth century usually being wheelocks while those produced by the middle part of the century were flint lock (Peterson 2000:40-41). These appear to have been popular weapons in the colonies with many references to them towards the middle part of the century, for example an inventory of the pieces in the arsenal of Maryland included 177 carbines and 613 muskets (Peterson 2000:41).

http://plymoutharch.tripod.com/id71.html

However, in making recommendations for firearms in particular, we are faced with the reality of members who use English lock weapons for Benjamin Church’s Company (and are perfectly correct flint weapons for this earlier period), and the reality of what is being recreated today, what is readily available without very expensive custom manufacturing. To be honest, although the .65 caliber was popular with the English right through the middle of the 18th century (for example, light infantry muskets in the Seven Years War were .65 caliber), nobody makes that caliber in a barrel. Nor is .58 caliber reproduced in early weapon reproductions. Basically, you have .62, .69, and .75 caliber. The shorter barreled weapons are also hard to get as harquebuses and carbines are not generally reproduced. You can get fowlers (very long barrels, longer than the musket length listed above) and muskets.

It is our intention to be as correct as we can without breaking the bank, so while the list above is instructive in what they had for firearms on the Piscataqua River in the 1630’s, we can only get what is available. Please consult Sutler and Sources list for recommendations.

Firearms

Matchlock, snaphaunce, English lock or wheellock are all acceptable. These can be any length or size available; muskets can use supporting stick or not.

Matchlock

Snaphaunce

English Lock

Wheelock

Pistols

You can see the list has only limited number of pistols, so we should keep these to a minimum in the company as well. There are some English lock pistols being reproduced.

Demonstration and Drill for Matchlock

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mrIQ59vRlvY

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSy3Bl32OvY

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yzf0ZiVr9qw

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1WwQkeDuXs

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=snGDtVDhJq8

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D67uvb_kxaY

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tCdnW6AaRw

Swords

The Plimmoth Gard put out a link about these. https://www.newplimmothgard.org/sword/

Essentially you should think in terms of rapier, basket hilt (broad or backsword), cutlass, or hunting sword. You can see from the list above that they had 100 swords and belts, but 256 handheld weapons, so it is not required that you have a sword.

Rapier

Basket Hilt

Cutlass

Hunting Sword

Pikes

We have found no evidence of pikes in any of the inventory lists. We are still trying to determine the meaning of a “beaver spear” mentioned in the 1635 list. For now, we are speculating that because it was listed with military stores it was essentially a half-pike, 6’-8’ long. Half pikes were topped with a spear point, of course.

Belt or Girdle

Men and women commonly wore a narrow belt, usually over the top of their doublet. The was ¾” or 1”, certainly not more than one inch. From this could be hung a utility pouch, knife, eating knife and pricker (see below).

Women wore them as well

Some had extra buckles with loops where hooks on the sword carriage could be hung, or easily removed when not in use. The extra slide buckle to the right side of the first figure is such a buckle. You can see how it works in the second figure, plus pictures from some reproductions.

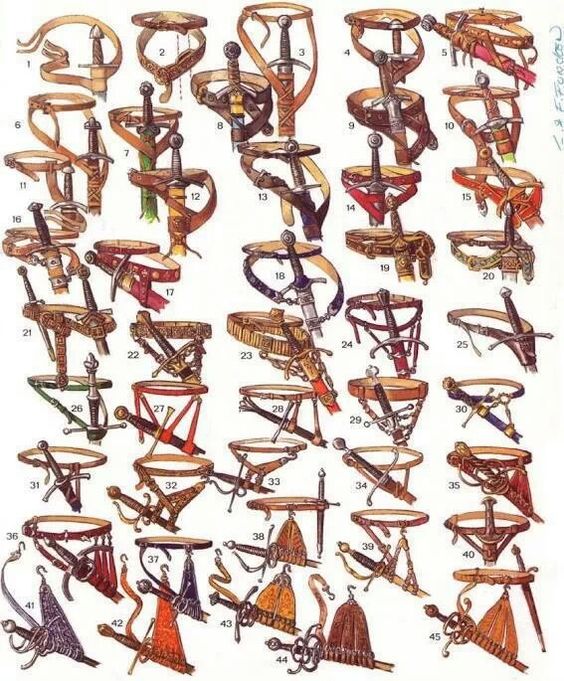

Sword Carriages

Which brings us to sword carriages. As indicated above, it is not required that you have a sword, but if you do, you must have some method of carrying it, and the list always has a “sword and belt” listed together

Baldric, Shoulder Style

Evidence seems to indicate that the predominate method of carrying swords in the early 17th century was with a waist carriage, and we could put way too much in the vocabulary of the inventory list when they say “belt” and not “baldric.” Shoulder baldrics were not unknown, just rare. You should keep that in mind.

This site sells them, but their pictures can provide ideas for those who work in leather.

http://www.lorifactor.com/k61,products-16th-18th-cent-baldrics.html

Here are two of their shoulder baldrics.

Karl Robinson, who makes the belt pouches described below, also makes sword carriages. Again, use this for purchase or inspiration.

https://www.karlrobinson.co.uk/other_stuff_buckles_baldrics.php?cat=54

Waist Carriage

These are so typical of the 16th/17th century, mostly connected to gentlemen and rapiers. The problem, as always when recreating the times before photography, the predominance of the evidence comes from paintings, and paintings were generally done with the upper class. There are many examples of fancy waist carriages with lots of buckles, but how common were they in the colonies? I don’t have an answer for that. As it often does, it comes down perhaps to creating a persona. There just weren’t many upper-class Englishmen coming to the colonies. However, according to the inventory lists the company did provide “swords and belts” for defense of the colony. Were these the carriages provided? Kudos to anyone who has the answer to that.

Source for sale and inspiration.

http://www.tattershallarms.org/gear.html

And for DIY types, here are lots of styles to choose from (mostly from the bottom half of the sketch).

Belt Pouch

For those who will be using flint weapons and loading with cartridges, you will need some kind of bag to hold them. Calivers and harquebuses were usually loaded directly from a flask, however this is unsafe. We will load from bottles or cartridges, even though cartridges were not used this early, but for safety we will use them. We will not be shooting that often, and some people are known to carry a few in the pockets of their breeches.

Karl Robinson in England makes these, but I can make them as well. Check Sources and Supply List.

Here are examples of what should be used if using for cartridges:

Now, another style of belt pouch is good for carrying small items, but not really convenient for cartridges.

Bandolier

This is the classic method of carrying shot and powder. Certainly, those with a musket should be carrying one, and any weapon can be loaded from a bandolier. They also give the look of the period.

Bandolier with attached powder flask

Bandolier without Primer, and so a separate powder flask had to be carried

Bandolier with wooden primer, hanging directly below the ball pouch. It has a tapered top. Note how extra match was often carried.

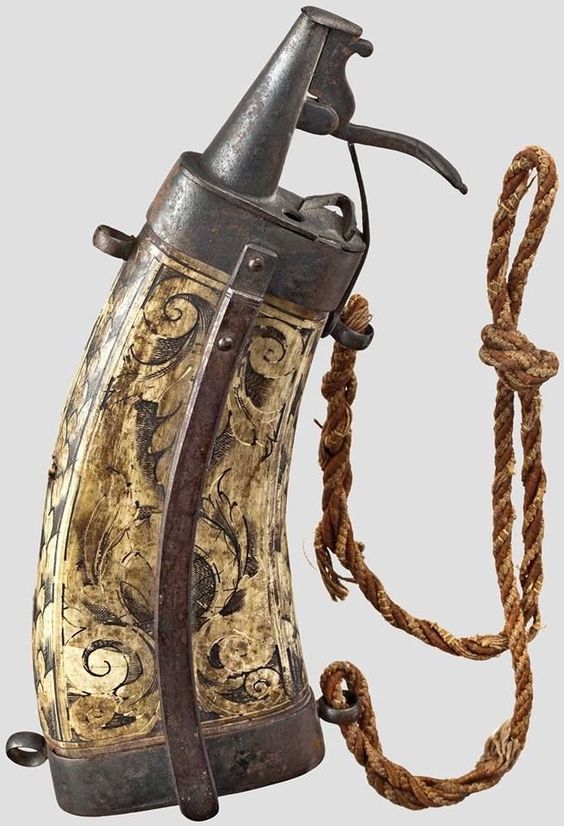

Powder Flask

Even if the bandolier had a priming bottle, soldiers often carried an extra powder flask on a separate strap just in case. Here are typical designs.

German, late 16th century with option of belt hook or shoulder strap.

Another with the belt hook or strap option. Apparently, many of them had this.

Knives

Fighting Knife

This would be the Main Gauche. It was positioned around the back with the hilt pointed toward the left side. The sword was drawn with the right hand and the Main Gauche draw with the left. How many English settlers had one of these is hard to know, probably few as most were farmers and tradesmen and they are not listed in the military inventories. Therefore, I would think long and hard before getting one. This is a pretty typical one.

Utility Knife

Eating Knives

Narrow and pointed so meat could cut and speared. Sometimes accompanied by a pricker to hold the meat, although often done with the spoon. Forks had actually been in use for quite a while, mostly it was the upper class in Europe. One article I read indicated that as forks were used more in Europe, the knives became wider and thus less pointed. Because forks were not used in the English colonies, when these wider bladed knives came over, people found they had to cut the meat with the knife, holding it with the spoon, and then switch the spoon to the right hand to scoop up the meat. This is where the American habit of cutting with the right and then switching the fork to the right hand to eat came about (and American spies in Europe in WWII had to be careful not to eat this way. A dead giveaway, and I mean dead).

Knife with pricker

Knife, pricker and 17th century spoon design

Snapsacks and Blanket Roll

These should be available to wear as well. It is one thing for a town drill, and another if called out for some service. The men on the Dixy Bull expedition were gone for almost a month. We should have something to carry food and a blanket.

The snapsacks are what most of us use already, leather or linen. They can be closed on one side or open on both sides.

17th century prints

Leather Snapsack

Vinnie at Bethlehem Trading Company has these in linen with linen or leather straps

Canteens

It is hard to know how often men carried water with them, since the water around them was remarkably unpolluted. Certainly, natives carried a small cup and trusted the lakes, streams and rivers. But we often need to hydrate. So, what is best for the 17th century?

The answer is a “costrel.” The costrel is identified with “ears” to hold the strap. It could be leather or pottery. BTW, the costrel was often tied to the belt, so the strapping was short, although shoulder straps are okay.

Camping Gear

Please look under Harmon’s Company of Snowshoemen or Eames’s Rangers for descriptions of how we camp.