In portraying New England snowshoemen, the militia laws provide a good beginning:

“Every listed souldier … shall be alwayes provided with a well fixt firelock musket, of musket or bastard musket bore, the barrel not less then three foot and a half long, or other good firearms to the satisfaction of the commission officers of the company, a snapsack, a coller with twelve bandeleers or cartouch-box, one pound of good powder, twenty bullets fit for his gun, and twelve flints, a good sword or cutlace, a worm and priming wire fit for his gun.” – Mass. Militia Laws, Nov. 22, 1693.

“every soldyer Shall be well provided w’th a well fixed gun or fuse, Sword or hatchet, Snapsack, Catouch box, horne Charger & flints” – New Hampshire Militia Laws, Oct. 7, 1692.”

“…That upon an Alarm made at any of the Frontiers, Forts or Garrisons, with the Province, on Advice or Discovery of the Indian Enemy coming upon or Appearing near the same, the said Officers and Snow-shoe Men, or so many of them as can be drawn together as the Circumstances of the Case may require, shall, pursuant to the Orders given them by the Commander in Chief, for the Time being, March out forthwith after the Enemy, well fitted with Arms, Ammunition, Provision, and each of them a Blanket, to Pursue, Encounter, Repell and Destroy the Enemy: and the said Officers & Soldiers so taking to Arms, besides the Wages and Subsistence allowed to the Marching forces in the Service and pay of the Government, shall be Entitled to such other Rewards in Case they obtain any Plunder, Scalp of the Enemy or Captives, as is by Law provided as a Premium or Bounty for those who go forth as Voluntiers, without pay ” Order creating Snowshoe Companies, May 24, 1724

Although these appear to be older, they didn’t change much over the years. As for the time period we are covering, think in terms of 1745-1760. Although most of the events we will be attending and forts we will visit will focus on the last French war (1754-1763)

One thing to consider as we proceed: although snowshoemen were under provincial pay and considered in his majesty’s service, they were not issued any equipment. You should consider what a man on the New England frontier would have available. This may mean items he made himself or procured locally for militia use. It is possible that equipment made for English army use could have made their way into the hands of New Englanders, say through service on various expeditions when the British government distributed old equipment. It could be that a relative served as well. However it is a good idea to avoid army issued equipment.

Weapons

One of the things that sets us apart is the fact that everyone has made an effort to get a weapon that is unique and correct for the 1740’s. It is best to keep in mind what was available to snowshoemen on the New England frontier in 1745. They had little access to state-of-the-art British military arms. Although the British government had at times shipped weapons over for Provincial forces, they tended to send older, out-dated weapons (cleaning out the storehouses). Most provincials used weapons that were 30-50 years old, even older. So, don’t think about weapons dated during the Seven Years War (which most French War reenactors do), you need to think about weapons from 1690-1730. Therefore, 2nd Model Besses are not acceptable, nor are Charleville muskets. We understand how prevalent these are in the hobby, most of us have owned them, but 2nd Model Besses did not come here until the American Revolution, and then only with the newer British regiments that came over. The regiments that were stationed in America still had 1st Models. The same can be said for the Charleville. We understand that individuals wishing to join may have to use a 2nd Model Bess or a Charleville temporarily while they get the rest of their gear, but understand that it is only temporary, and you must get a proper weapon as soon as possible.

Acceptable: Long fowler (club butt in particular), Early British Musket (doglock, Queen Anne, or 1728 First Model Brown Bess), Dutch muskets or trade guns, French Tulle fusil de chasse, fusil du fin, or fusil du roi, early French or English trade gun.

The unit is now operating in four time periods: The Piscataqua Company (early 17th century) Benjamin Church’s Company (late 17th century), John Harmon’s Company of Snowshoemen (1740s-1750s) and Jeremiah Eames’ Rangers (early Rev War). Harmon’s Snowshoemen is the primary unit, and you should focus on that, but if you have interest in doing all four, you will need two weapons. An English doglock or Type C French trade gun (Fusil de Chasse) will work for Church’s. Harmon’s and Eames’s Companies. One rule of thumb, if you want a weapon to be acceptable for Church’s Company, it cannot have a frizzen/pan bridle. While this bridle makes it easier to attach a flashguard, they did not come in until the 1720s or 1730’s. Also be aware that a doglock must have an internal half-cock notch. The dog can only serve as a supplementary half-cock safety.

Okay: Later First Model Brown Bess (1742, 1755). But understand that that it is highly unlikely that a New England provincial soldier would have a new model British weapon. At least try to stick with a version that has a wooden ramrod.

Accoutrements

Cartridge Box or Hunting Pouch w/ powder horn: Obviously, you need something to carry cartridges in. Hunting pouches were most common. These tended to be a square or rectangular rather than the rounded types of the later Revolutionary war period, or beaver tail style of later periods of the middle colonies. Fort Ti has been requiring a wooden clock with drilled cartridge holes for hunting pouches, most sites do not.

Cartridge Boxes were also used, in fact, a list of petitions New Hampshire widows presented in 1746 for gear lost by husbands in the attack on the Island Battery at Louisbourg in 1745 shows that most carried cartridge boxes rather than “show pouches.”. As indicated, you probably should avoid a brand-new British cartridge box. Something old and out of style would work. These should be British style, with large flap. Strap should be buff or undyed leather, 2 3/4″ or 3″ wide, preferably with three buckles. Better still it could also be something with a homemade appearance. Neumann and Kravic’s Collector’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution show many versions of American made cartridge boxes. Belly boxes are also acceptable, but remember that they carry limited rounds, and rarely sufficed as the only method of carrying rounds. They could be worn to augment either a shoulder box or hunting pouch.

If you carry a hunting pouch you should carry a powder horn. Powder horns are also acceptable with cartridge boxes. You cannot actually have powder in a horn during a reenactment.

Sword or hatchet: As you can see from the militia acts, soldiers were encouraged to wear a sword or cutlass, however a member of a snowshoe company would likely carry a hatchet as being more practical in the woods. Some sort of edged weapon is encouraged. If you opt for a sword, stick to the shorter styles, including hangers, hunting swords and short cutlasses. A survey of petitions from family who lost men at the attack on the Island battery at Louisbourg in 1745 showed about half had swords and half had hatchets, with a couple listing both. However, they were volunteers for an expedition, not going on a scout in the woods.

Waistbelt or shoulder belt carriage: Obviously, if you carry a sword of hatchet, you will need a way to carry them. This can be a waistbelt or a shoulder belt style. Choose styles appropriate to the French war period (usually buff with a wider belt). You can stick a hatchet in a regular belt or tie it to your pack, but a sword will need a carriage. Bayonets are problematical. Muskets were issued with bayonets, called a “stand”, but would they be carried by a snowshoe man on a scout? What would be the purpose of the extra weight? Don’t bother.

Buckles: There is some controversy about whether iron buckles were used. Brass buckles survive under ground and have been found in numerous archaeological sites, but the iron tines have rusted away. Iron buckles may have also been used by civilians, but did they rust away? Certainly, we know that the prevalent wrought iron buckles that are thick and wide in an oval or round shape are not correct. Use brass or a more delicate square iron buckle.

Canteen: This could be tougher. Again, the rule of thumb is that snowshoemen did not have equipment issued. Frankly, we are not even sure if they carried canteens on a scout. Streams and rivers are plentiful in New England and they didn’t give a thought to pollution. A simple cup would have supplied water. However, the reality is that we have to carry our water. The easiest canteen to get is the tin kidney shaped, but how many provincials would have a British style canteen? These were made for British army under contract. If you get a tin canteen (which is the easiest and cheapest), you should disguise it somehow. Cover it with wool cloth and replace the white cord with natural hemp rope or leather. However, better choices would include wooden canteen, wooden barrel (rundlet), leather “jackware”, or a period bottle covered in leather.

Haversack: Again, we have no information on how snowshoemen carried their food. In winter they pulled sleds, but on summer scouts we just don’t know. Most reenactors think of the haversack for carrying food, but the whole concept is tied to military organizations. In fact, the term “haversack” is controversial in reenacting circles if not specifically a food bag issued by a government to regular troops. Perhaps the most authentic approach is to carry your food in your snapsack or knapsack (most of us do that). However, if you want to have a separate bag for food try to avoid any appearance of army issue. Don’t get a square, natural color haversack with three pewter buttons (please, don’t even consider the white canvas haversacks available from many sources). Make it look unique or home made, a simple bag made from a heavy linen with a strap and bone or antler buttons.

Knapsack/Snapsack/Rucksack and Blanket Roll: Always keep in mind that you are portraying soldiers who were away from home for extended periods of time. Snowshoemen were to turn out with provisions and a blanket. You should have this appearance. We try to portray the snowshoemen as if they were always on a scout. You should have some method of carrying blanket and extra clothes. A blanket rolled in an oil cloth, with your spare clothes rolled inside, works well. Or a blanket roll and a snapsack (a long, narrow leather or cloth bag with a strap that opens on the end), which can carry the clothes and your food. You could use a knapsack which was a bag that opened on the top instead of the end. These could be a larger haversack style with a single or double strap or create a double bag effect with a strap running though it. A third option is a rucksack, a simple bag tied at the top and bottom corners with the shoulder strapping. Most members carry a blanket roll and some sort of homemade knapsack, snapsack or haversack. They have found something that works well for them. Remember we like to keep all our gear with us, giving the impression that we are just back from or ready for a scout, so less is more.

Clothing

Some basics concerning clothing and materials. Stick to linen, wool or leather. Cotton was an expensive import cloth at the time, linen was plentiful and cheap. Unfortunately, the opposite is true today, which will add to the cost of your outfit, but get a linen shirt. There are many websites dedicated to 18th Clothing and materials. Beth Gilgun’s book: Tidings from the 18th Century is the best basic source for clothing that we have found. Wool was the most common cloth for outer clothing, but linen was not unknown.

Hat: There are several styles and options: The best bet is a simple hat with broad brim, either flat or cocked into a tricorn hat. It may be bound with tape or unbound. The cocked hats were so common that many of us have one to wear around except when going into the woods on a scout. The felt hat with the brim down, or even cut back to a couple of inches (the British army did this in last French war) is most convenient when going into the woods or out in the blazing sun. A knitted Monmouth cap or working man’s cap sewn from linen might work, although more for lounging around. Hats to avoid: bicorne Rev War, ranger hats, either cut down felt with front flap turned up or highland bonnets (we want to distinguish ourselves from rangers, and there were very few Scottish Highlanders in New England at this time). Another usage that should be avoided because we simply don’t know how widespread it was in northern New England is the sticking of feathers in the hat. Yes, we know about Yankee Doodle Dandy, but the jury is presently out on this. Best avoid it until we know more.

Shirt: linen, 18th century style, white, striped or checked (as long as it is a woven check and not printed).

Neckcloth: Some sort of linen cravat should be part of the outfit, at least when not on a scout. This is a simple narrow band of linen tied around the neck.

Coat: One thing that will be required is some sort of garment with sleeves. Remember, you have been called into service for a raid or expedition; it is unlikely you would go in just a shirt. French war reenactors will sometime just appear in shirts, or shirt and sleeveless waistcoat, and they have the look of an unmade bed about them. We will always have a coat or jacket with sleeves.

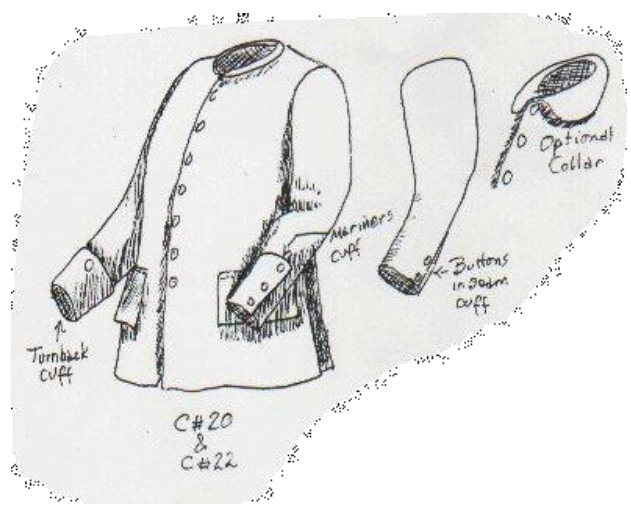

Having said this, there are several options. One would be the standard civilian coat of the period. What is this exactly? It should reach down to at least the knees, formal coats had no collar, frocks (made for everyday, outdoor wear) were less stiff in construction and often had a wide collar (2″ to 3″) that lay down on the coat, called a cape. Cuffs are optional but should be about 4″-7″ wide with four buttons holding it to the sleeve. You can have a wider cuff, but this would be an older fashion (1730’s) and should not look like a new coat. Cuffs of 3″ came about during the Rev War period and so should be avoided. Coats without cuffs often had a buttoned slit on the side. Coats should be made of wool or heavy linen.

A second choice would be the sailor or workman’s jacket. These were shorter (just covering the butt), and rarely had collars or cuffs (although employed split sleeves). They were generally made of wool and made pretty crude. Finally, there is the sleeved waistcoat.

Buttons for coats and jackets can be pewter (plain or with design, or covered in matching cloth), leather, or crudely made bone or horn (for workman’s jackets), or wool.

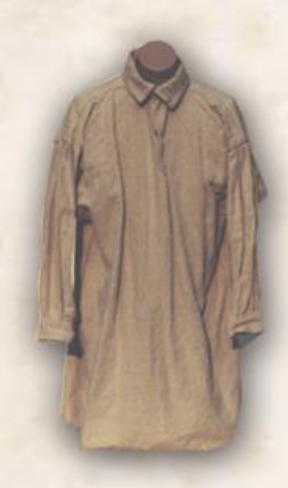

Work Shirts: Long, loose linen work shirts are nice to wear around camp, or even in the field when hot (although you must have some sort of coat or jacket as well). These are made with heavy linen and can be pull-over or slit up the front (pull-over style was most common in New England). But DO NOT wear heavily fringed shirts with capes. They are Rev War period and come from Pennsylvania/Virginia originally, not New England. New England farmers had coarse linen work shirts, not fringed hunting shirts.

Waistcoat: Waistcoats were fairly long and cut straight in the front, unlike the Rev War period when the front of the waistcoat cut away. [see pictures of frock coats above] Ideally, the length in front should cover the fly of the breeches. The back can be the same length as the front or several inches shorter (there are examples with no back skirts at all). The center back seam sometimes was slit up to the shoulder blades and were laced (eye holes running along the edges of the slits) or had ribbon ties. The back could be made from different material than the front (usually cheap or coarse linen). However, if meant to be worn without a coat (especially if it has sleeves) then the back should be the same material as the front.

Sleeved waistcoats were popular hot weather wear. British regulars had sleeves on waistcoats for that purpose. Generally, the sleeves ran short (so they would not show if the coat was worn) and had a short slit in the under seam with a single button closure. If you are opting for a sleeved waistcoat as your primary outer garment, I recommend wool. Otherwise the waistcoat can be either linen (natural, striped, etc.) or wool.

Breeches: Breeches underwent a significant transformation in the mid-18th century, from button fly to flap front. The transition date is right around 1750, so we have some options. As the flap front style was just coming in, the button front, sometimes called the “French Fly,” was probably more prevalent, however, the flap front is perfectly acceptable. Like weapons, you may want to think about other uses. If you are only going to use these for French war, get the button fly, if you might wear them for Rev War, get the flap front. The bottom band on the leg can be closed with either a buckle or button, or cheaper breeches for working men still had a simple tube with a tie running through it. As for material, again you can use linen (natural, gray, brown, blue, striped), wool (more common), or leather. Leather breeches were quite common; in fact, there were people known as “Leather Breeches Makers” because that was all they made. Working men and farmers found them durable. Unfortunately, leather was far more common and far cheaper in the 18th century. You will find leather breeches expensive today, but very authentic, and yes, very durable and hot! Another option is sailor’s pants made from canvas or linen but should be kept to a minimum. Note on Rev War Breeches: I’m sorry, but the common white cotton breeches worn by many reenactors are not acceptable. Not only is the material wrong, but bright white breeches don’t mix with scouting in the woods.

Socks: Knee length Linen or wool. Stay away from bright white socks. Off white, brown or blue are preferred. Almost every sutler sells them. Winter soldiers will want to invest in several well-made woolen stockings, or footless hose.

Leggings: We have been unable to find any references to leggings or gaiters used by provincial soldiers. However, having said that, running around in the woods can tear the hell out of your socks. You have several options: Full Gaiters (over the knee) that button the whole way, made from wool or painted canvas (paint them after you make them, use brown or black). Buttons can be pewter, wood, bone or horn; Indian style leggings made of leather or wool sewn with flaps down the outside; or simpler wool leggings wrapped and tied around the leg. In this, as in so many of these items, you should think about what you would do if you lived at that time. Would you wear leggings or gaiters, and what style do you prefer?

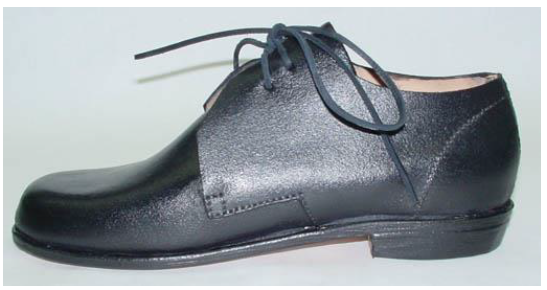

Shoes: low cut buckle shoes, low cut tie shoes, or moccasins. Some wear so-called low boots (shoes that extend above the ankle), sometimes called Hi-Lo boots. For those who have an old pair of buckle shoes that have loosened up, poking holes in the flaps and tying them with leather thongs will make them tighter. One solution that works for all four time periods are low cut tie shoes. Many of us have success with C&D Jarnagin War of 1812 low cut shoes. Yes, War of 1812, but they look just like any common tie shoe and they are very well made (they better be for the price!)

Glasses: If you need glasses, you must have authentic style frames or contacts. The two worst anachronisms seen on less authentic reenactors are modern glasses and shoes…these items stick out like a sore thumb. There are several versions available. This style is the most acceptable:

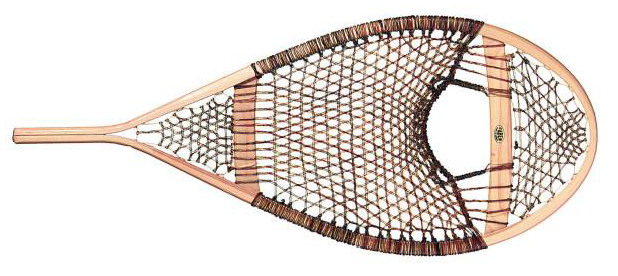

Winter Clothes and Gear: Some members do late fall even winter scouts and snowshoe trips, so you may want to consider winter gear. This would include some kind of great coat or matchcoat (a way to tie a blanket around you), knitted, cloth or leather with fur mittens, scarf (best simply a strip of tightly woven wool cloth), and Canadian hat or wool Monmouth cap. Heavy wool socks are obvious, and high shoes, like Soulier de Boeuf or something similar. Some get moccasins that are a bit large and put heavy liners made from old blankets. Members can advise on all of this when you need to acquire these items. Finally, snowshoes must be wooden with rawhide lacing. There are sources for reproduction snowshoes. Your bindings should not be modern. You can use leather strips or hemp rope to tie on your shoes. Members can show you how.

Final Notes: Just try to be original and stay away from copying others too much. We need to avoid the appearance that our clothing and equipment was issued, and thus all the same. Brown coats, for example, proliferated in the group. Brown was a very common color, but if everyone wears brown it begins to look like a uniform.

New Englanders were often described as wearing “sad” or muddy colors. So, shades of gray, black, dark blue would be fine as well. Please also be aware that many of us read about and interact with so-called “historical trekkers,” or longhunters. This portrayal is quite specific to a time and place, but not for New Englanders in the 1740’s and 50’s. Many aspects we do hold in common, such as woods knowledge, food, fire-starting, etc., but other aspects, especially clothing, do not carry over.

New Englanders should also be particularly concerned about using native clothing and adornments. We are portraying men who defended their loved ones and homes from the Indians. These men were Englishmen, and Christians, and frankly, pretty prejudiced against Indian culture in general. They adopted native culture that made sense and was practical, such as leggings, moccasins, and of course the very tactics that they used, but there is no evidence, nor is it even conceivable, that they wore breechclouts, hand-loomed multi-colored sashes or adorned themselves with beads, bells, or Wampum.

Camping Gear

Cooking Gear: We have decided to treat food and cooking as if we were on a scout, which means every man brings his own. We have communal fires, and everyone has personal cooking equipment. One advantage to this is that if any of the group wants to participate in French War tacticals (which can run several days) or organize a scout (called a “trek” in other circles), you already have your equipment. The following is a suggested list. Experience will be your best guide. Most think in terms of “What am I willing to carry on my back for any length of time?” Some eliminate the need for almost all cooking by relying on dried food (jerky, parched corn, dried fruit, etc.).

The most authentic way to cook is with a brass pot (tinned lined, of course). Scouts often used a communal pot and this can happen as well.

To be honest, when we started out most of us got the following items: Fry Pan – The small pans with folding handles that can be packed easily get a great deal of use. Meat, bacon, or small stews can be easily whipped up. Corn Boilers – Small copper, tin or brass cook pots of varying sizes (you can get nesting ones that provide several sizes). Good for hot cereals in the morning, stews and coffee water. Squirrel Cooker – this is a two piece, forged set, one an upright with a loop, the other a long fork that slides through the loop and extends over the fire. They can be used to cook hunks of meat.

However, the historical accuracy of the folding fry pan, corn boiler and squirrel cooker has been called into question. If truly on a scout you can use one communal pot, and rather than risk sticking yourself with your squirrel cooker, simply use a sharpened stick. However, in a base camp such as a reenactment, the fry pans and the squirrel cookers still get a work-out.

Similar is the small folding grate. Frankly, if in the woods you can cook using firewood for support, but most of us have purchased these folding grates. The reality is that we tend to use one or two grates, and the rest leave theirs in their cars. If you want to cook on your own sometime, it is probably worth the investment, but you might just find yourself leaving it at home, trusting to someone else’s grate or the old firewood trick.

Utensils – You should have the usual utensils, spoon, folding knife, fork. Most of us have some form of trade or utility knife and a spoon. You can prepare and eat most things with that. By the way, a short utility knife will get far more use than a large hunting knife.

Coffee – This you can heat up in your brass kettle or boiler, however, several of us have period coffee pots and boil up communal coffee. Snowshoemen Need Their COFFEE!

Sleeping Gear: Here we run into a roadblock created by reenactors. Frankly, New England Provincials, particularly those on the frontier, did not have military style tents. Since the colonies had no standing army, there were no industries in existence to make military gear. England had companies that provided such goods (in essence workers who hand sewed linen canvas into tents), but not the colonies. The only time New Englanders had true military tents is when the British army was present and gave them their old tents (which usually leaked). What did provincials stay in? More importantly, what did snowshoe men on a scout stay in? As to the latter, that is easy, they did what anyone did in the woods, slept in the open in good weather, slept in brush or bark shelters in bad weather. They certainly didn’t lug tents with them. Even when not on a scout, but involved in more formal operations, improvisation was the rule.

From Fred Anderson’s A People’s Army about provincials in the last French war. Robert Treat Paine, the Chaplain of Colonel Samuel Willard’s Regiment, described the provincial camp at Lake George in 1755 “In one part you might behold rows of habitations appearing like white sepulchres … in another part you might see a cave or hole in the rocks; some huge pole of brush and dirt to fend off the cold and rain – others had long rows of buildings that much resemble meeting house sheds.” Paine conveyed a fair impression of the variety of tents, burrows, longhouses, and bow-houses that made shift for housing in the provincial camp. …From the standpoint of uniformity, the uncontrollable impulse to build was bad enough; but the competitive individualism implicit in wanting to build “the biggest house in the regiment” was potentially much worse. Predictably enough, the desire for outsize houses did not stop with privates. In 1758 Colonel Jedediah Preble employed thirty men to build his house at Lake George. …”

The fact was that, no matter how unmilitary, potentially unhealthful, and unquestionably irregular soldier-built housing was, it offered at least as much protection as the tents. As I said, most of the tents given provincials came from British regiments who had just received new ones. The old, ripped leaking ones were given to their colonial compatriots. No wonder they made their own. But it also indicates that they were used to this; that living in tents was not a normal part of their military experience.

So, what shelters do we use? Everything from none (roll out a blanket and sleep under the stars), to oil cloth lean-tos. Some occasionally still use military A-tents, but it is event specific. They are used at the Old Sturbridge Village event because that is the one event where men bring wives and families, or at an event where we portray a town militia instead of a scouting company. One note: You should stay away from any canvas shelters that have brass grommets. Brass grommets are not accurate.

Blankets: You will also need a good wool blanket. Some members have very expensive hand-woven reproductions, while others have army surplus specials. 18th century blankets were woven on narrow looms and had a center seam where two lengths were sewn together. Surprisingly, these do turn up on eBay, mostly from Canada. A good white wool blanket will do. Avoid candy stripe or loud colored Hudson Bay styles.