Eames’s Rangers had no clothing, weapons or gear issued to them that we know of. Everything they carried was personally owned.

Firearms

One note, the Second Model Bess did not come here until the newer British regiments began to arrive. The regiments already here still had First Models. Now, American privateers began to capture British supply ships, that is true, but the idea that any captured muskets made their way to some raggedy-assed New Hampshire rangers is unlikely in the extreme. Stay way from the Second Model Bess.

Acceptable: Long fowler (club butt in particular), Early British Musket (dog lock, Queen Anne, or 1728, 1742 or 1755 First Model Brown Bess), Dutch muskets or trade guns, French Tulle fusil de chasse, fusil du fin, or fusil du roi, early French or English trade gun. [Note: doglocks must have the internal half-cock notch and not rely on the dog for half-cock. This is a safety inspection issue at some events]

Okay: Well, barely okay, French Charleville musket … not the best, but better than the Second Model Bess.

Accoutrements

Cartridge Box or Hunting Pouch w/ powder horn:

Obviously, you need something to carry cartridges in. Hunting pouches were most common, used with a powder horn (You cannot have powder in a horn during a reenactment). You should stay away from the smaller rifle pouches. Rifles were not used by these men and those pouches tend to be from Pennsylvania and Virginia. Think in terms of a homemade leather bag for ball and shooting supplies.

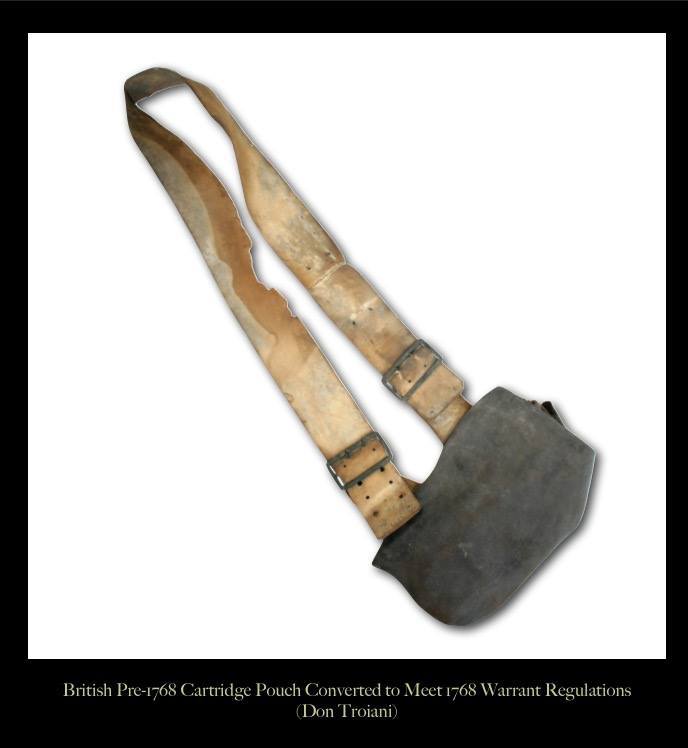

Cartridge Boxes were also used. As indicated, you probably should avoid a brand-new British cartridge box. Something old and out of style would work. These should be British style, with large flap. Strap should be buff or undyed leather, 2 3/4″ or 3″ wide, preferably with three buckles. Better still it could also be something with a homemade appearance. Belly boxes are also acceptable, but remember that they carry limited rounds, and rarely sufficed as the only method of carrying rounds. They could be worn to augment either a shoulder box or hunting pouch.

Neumann and Kravic’s Collector’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution show many versions of American made cartridge boxes and hunting pouches.

Sword or hatchet:

Although prevalent earlier, we have no idea how many swords were carried by units like Eames’s Rangers. Hatchets would make more sense, but swords are not forbidden. If you opt for a sword, stick to the shorter styles, including hangers, hunting swords and short cutlasses.

Waistbelt or shoulder belt carriage:

Obviously, if you carry a sword of hatchet, you will need a way to carry them. This can be a waistbelt or a shoulder belt style. Choose styles appropriate to the French war period (usually buff with a wider belt), as this would be more common than current military carriages of 1776. You can stick a hatchet in a regular belt or tie it to your pack, but a sword will need a carriage. If you are carrying a military musket, it would not be outside the realm of possibility for you to have a bayonet (muskets were issued with bayonets, called a “stand”).

Buckles: There is some controversy about whether iron buckles were used. Brass buckles survive under ground and have been found in numerous archaeological sites, but the iron tines have rusted away. Iron buckles may have also been used by civilians, but did they rust away? Certainly, we know that the prevalent wrought iron buckles that are thick and wide in an oval or round shape are not correct. Use brass or a more delicate square iron buckle.

Canteen:

This could be tougher. Again, the rule of thumb is that frontier rangers did not have equipment issued. Frankly, we are not even sure if they carried canteens on a scout. Streams and rivers are plentiful in New England and they didn’t give a thought to pollution. A simple cup would have supplied water. However, the reality is that we have to carry our water. The easiest canteen to get is the tin kidney shaped and possible service in the last French war makes these more reasonable. You should disguise it somehow. Cover it with wool cloth and replace the white cord with natural hemp rope or leather. However, better choices would include wooden canteen (barrel or cheese box), wooden barrel (rundlet), leather, or a period bottle covered in leather.

Haversack:

Again, we have no information on how rangers carried their food. Most reenactors think of the haversack for carrying food, but the whole concept is tied to military organizations. In fact, the term “haversack” is controversial in reenacting circles if not specifically a food bag issued by a government to regular troops. Perhaps the most authentic approach is to carry your food in your knapsack. However, if you want to have a separate bag for food try to avoid any appearance of army issue. Don’t get a square, natural color haversack with three pewter buttons (please, don’t even consider the white canvas haversacks available from many sources). Make it look unique or home made, a simple bag made from a heavy linen with a strap and bone or antler buttons and call it a bag not a haversack.

Knapsack and/ or Blanket Roll:

Always keep in mind that you are portraying soldiers who were away from home for extended periods of time. You would have food, perhaps extra clothing and a blanket. You should have this appearance. There is a little controversy concerning Rev War period knapsacks that were personally made and not issued. The 18th Century New England Life website provides some information. Here are some simple thoughts:

Knapsacks: This could be a single strap version from the last French War, a haversack style sack converted to knapsack by replacing the single strap with a double shoulder strap (these were often painted and used by militia companies), or any other kind of homemade devise.

Snapsack: There is some evidence of “snapsacks” being listed by soldiers as used or lost in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Whether these snapsacks represented the long tube form of carrier that opened on the end is unknown at this time. Although we allow them, at some point you may want to distinguish between the earlier snapsack (which is appropriate for all three earlier units) and the Rev War period.

Market Wallet: Although certainly these can be conceived as used on April 19th, as the name indicates this was a device used to carry food on a leisurely walk to market. Hanging loose on your shoulder as it does is a royal pain humping through the woods. We don’t recommend them for our portrayal.

Clothing

Some basics concerning clothing and materials. Stick to linen, wool or leather. Cotton was an expensive import cloth at the time, linen was plentiful and cheap. Unfortunately, the opposite is true today, which will add to the cost of your outfit, but the price of a good linen shirt will end up about the same as a cotton one.

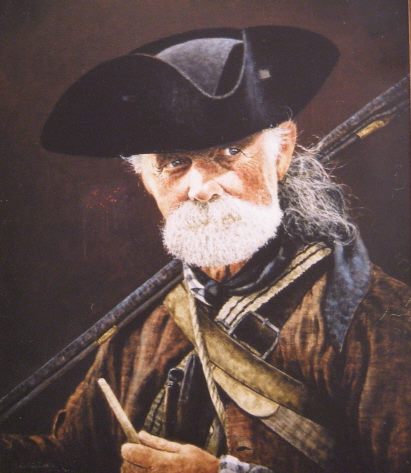

Hat: There are several styles and options: The best bet is a simple hat with broad brim, either flat or cocked into a tricorn or bicorn hat. It may be bound with tape or unbound. The cocked hats were so common that many of us have one to wear around except when going into the woods on a scout. The felt hat with the brim down, or even cut back to a couple of inches is most convenient when going into the woods or out in the blazing sun. A knitted Monmouth cap or working man’s cap sewn from linen might work, although more for lounging around. Hats to avoid: French War ranger hats, either cut down felt with front flap turned up or highland bonnets. Another usage that should be avoided because we simply don’t know how widespread it was in northern New England is the sticking of feathers in the hat. Yes, we know about Yankee Doodle Dandy, but the jury is presently out on this. No feathers.

Shirt: linen, 18th century style, white, striped or checked (as long as it is a woven check and not printed).

Neckcloth: Some sort of linen cravat should be part of the outfit, at least when not on a scout. This is a simple narrow band of linen tied around the neck.

Coat: One thing that will be required is some sort of garment with sleeves. Remember, you have been called into service for scouting; it is unlikely you would go in just a shirt. We all know the image of the sturdy yeoman farmers at Lexington and Concord just wearing waistcoats, but in all honesty, it was pretty chilly in April. It is doubtful they looked like that.

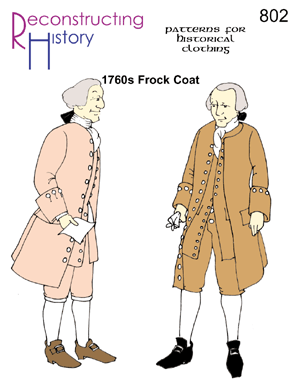

Frock Coat: This is the standard civilian coat of the period. What is this exactly? It should reach down to at least the knees, formal coats had no collar, frocks (made for everyday, outdoor wear) were less stiff in construction and often had a wide collar (2″ to 3″) that lay down on the coat, called a cape. Cuffs are optional. While it is conceivable that men were wearing older coats with wider cuffs (5”-6”), by the 1770s most cuffs had been shortened to about 3”-4”. Coats without cuffs often had a buttoned slit on the side. Coats should be made of wool or heavy linen. There were unlined linen coats as well. In addition, remember to think of “sad” colors. No bright greens, blues or red. New Englanders were known for “sad” colors. We had a new recruit buy a bright blue coat once that I think was observed by the space station.

A second choice would be the sailor or workman’s jacket. These were shorter (just covering the butt), and rarely had collars or cuffs (although employed split sleeves). They were generally made of wool and made pretty crude.

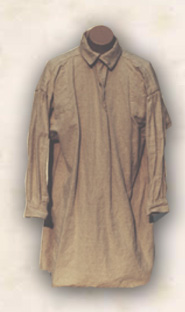

Buttons for coats and jackets can be pewter (plain or with design, or covered in matching cloth), leather, or crudely made bone or horn (for workman’s jackets), or wool.

Work Shirts: Long, loose linen work shirts are nice to wear around camp, or even in the field when hot (still worn over your regular shirt). These are made with heavy linen and should be pull-over as this style was most common in New England. DO NOT wear heavily fringed shirts with capes. They came from Pennsylvania/Virginia originally, not New England. New England farmers had coarse linen work shirts, not fringed hunting shirts. You must have some kind of coat for the unit, but the work shirt does come in handy.

Hot day! Out came the work shirts!

Waistcoat: Waistcoats had gotten shorter and the skirts were cut away unlike the earlier waistcoats, probably due to the switch to flap front breeches instead of the French button fly. The waistcoat can be either linen (natural, striped, etc.) or wool.

Breeches: Breeches underwent a significant transformation in the mid-18th century, from button fly to flap front. The transition date is right around 1750. Most men were wearing the flap front breeches by 1775. The bottom band on the leg can be closed with either a buckle or button, or cheaper breeches for working men still had a simple tube with a tie running through it. As for material, again you can use linen (natural, gray, brown, blue, striped), wool, or leather. Leather breeches were quite common; in fact, there were people who were known as “Leather Breeches Makers” because that was all they made. Working men and farmers found them durable. Unfortunately, leather was far more common and far cheaper in the 18th century. You will find leather breeches expensive today, but very authentic, and yes, very durable and hot! Note on Rev War Breeches: I’m sorry, but the common white cotton breeches worn by many reenactors are not acceptable. Not only is the material wrong, but bright white breeches don’t mix with scouting in the woods.

Trousers: Long trousers with flap front were also becoming more common. Although they can be worn by themselves, overalls were often used as work shirts and worn over breeches for protection in work. Don’t wear the gaitered overalls as these came in later and are connected to regular army usage.

Socks: Knee length Linen or wool. Stay away from bright white socks. Off white, brown or blue are preferred. Almost every sutler sells them.

Leggings: Here we once again have little in the records to draw from, especially as it concerns the full over knee buttoned gaiters. The British army went to the short gaiter in the Rev War. For men living on the New Hampshire frontier heading out to do scouting duty it is conceivable they wore something, running around in the woods can tear the hell out of your socks. There is evidence of so-called “farmers gaiters’ worn to protect low shoes and keep dirt and stones out. If you opt for these try to make them not appear military issue. Don’t make them black canvas with pewter buttons. Use wood, bone or horn. Make them from wool, make them brown or gray. Indian style leggings made of leather or wool may have been still in use; or simpler wool leggings wrapped and tied around the leg. The over-the-knee leggings do tend to say, “French and Indian War,” but we just don’t know if they were being used by such a unit. I can’t see them saying, “Well, they work really well, but they are so out of fashion. People will talk.” In this, as in so many of these items, you should think about what you would do if you lived at that time. Would you wear leggings or gaiters, and what style do you prefer?

Shoes: low cut buckle shoes, low cut tie shoes, or moccasins (except for Battle Road). Some wear so-called low boots (shoes that extend above the ankle, sometimes called Hi-Lo boots). For those who have an old pair of buckle shoes that have loosened up, poking holes in the flaps and tying them with leather thongs will make them tighter. One solution that works for all four time periods are low cut tie shoes. Many of us have success with C&D Jarnagin War of 1812 low cut shoes. Yes, War of 1812, but they look just like any common tie shoe and they are very well made (they better be for the price!)

Glasses: If you need glasses, you must have authentic style frames or contacts. The two worst anachronisms seen on less authentic reenactors are modern glasses and shoes…these items stick out like a sore thumb. There are several versions available. This style is the most acceptable:

Final Notes: Just try to be original and stay away from copying others too much. We need to avoid the appearance that our clothing and equipment was issued, and thus all the same. New Englanders were often described as wearing “sad” or muddy colors. So, shades of gray, black, dark blue would be fine as well.

Examples

No. 1: Flat hat turned up in back, blanket roll, homemade knapsack, leather canteen, hunting pouch and horn, early Queen Anne musket, workman’s jacket, overalls, and low boots.

No. 2: Blanket roll with spare moccasins, homemade knapsack, cooking pot, tricorn hat with workman’s cap underneath, shoulder cartridge box (see strap), short workman’s jacket.

No 3: Workman’s jacket, cut back waistcoat, flat cap with cut back brim, shoulder cartridge box, farmer’s gaiters, long fowler.

Camping Gear

Cooking Gear: We have decided to treat food and cooking as if we were on a scout, which means every man is brings his own. We have communal fires, and everyone has personal cooking equipment. The following is a suggested list. Experience will be your best guide. Most think in terms of “What am I willing to carry on my back for any length of time?” Some eliminate the need for almost all cooking by relying on dried food (jerky, parched corn, dried fruit, etc.).

The most authentic way to cook is with a brass pot (tinned lined, of course). Scouts often used a communal pot and this can happen as well.

To be honest, when we started out most of us got the following items: Fry Pan – The small pans with folding handles that can be packed easily get a great deal of use. Meat, bacon, or small stews can be easily whipped up. Corn Boilers – Small copper, tin or brass cook pots of varying sizes (you can get nesting ones that provide several sizes). Good for hot cereals in the morning, stews and coffee water. Squirrel Cooker – this is a two-piece, forged set, one an upright with a loop, the other a long fork that slides through the loop and extends over the fire. They can be used to cook hunks of meat.

However, the historical accuracy of the folding fry pan, corn boiler and squirrel cooker has been called into question. If truly on a scout you can use one communal pot, and rather than risk sticking yourself with your squirrel cooker while walking along, simply use a sharpened stick. However, in a base camp such as a reenactment, the fry pans and the squirrel cookers still get a work-out.

Similar is the small folding grate. Frankly, if in the woods you can cook using firewood for support, but most of us have purchased these folding grates. The reality is that we tend to use one or two grates, and the rest leave theirs in their cars. If you want to cook on your own sometime, it is probably worth the investment, but you might just find yourself leaving it at home, trusting to someone else’s grate or the old firewood trick.

Utensils – You should have the usual utensils, spoon, folding knife, fork. Most of us have some form of trade or utility knife and a spoon. You can prepare and eat most things with that. By the way, a short utility knife will get far more use than a large hunting knife.

Coffee: This you can heat up in your brass kettle or boiler, however, several of us have period coffee pots and boil up communal coffee. In fact, that is the practice.

Sleeping Gear: Here we run into a roadblock created by reenactors. Frankly, New England units, particularly those on the frontier, did not have military style tents. Since the colonies had no standing army, there were no industries in existence to make military gear. England had companies that provided such goods (in essence workers who hand sewed linen canvas into tents), but not the colonies. What did New Hampshire rangers on a scout stay in? As to the latter, that is easy, they did what anyone did in the woods, slept in the open in good weather, slept in brush or bark shelters in bad weather. They certainly didn’t lug tents with them.

So, what shelters do we use? Everything from none (roll out a blanket and sleep under the stars), to oil cloth lean-tos. Some occasionally still use military A-tents, but it is event specific. They are used at the Old Sturbridge Village event because that is the one event where men bring wives and families, or at an event where we portray a town militia instead of a scouting company. One note: You should stay away from any canvas shelters that have brass grommets. Brass grommets are not accurate.

Blankets : You will also need a good wool blanket. Some members have very expensive hand-woven reproductions, while others have army surplus specials. 18th century blankets were woven on narrow looms and had a center seam where two lengths were sewn together. Surprisingly, these do turn up on eBay, mostly from Canada. A good white wool blanket will do. Avoid candy stripe or loud colored Hudson Bay styles.